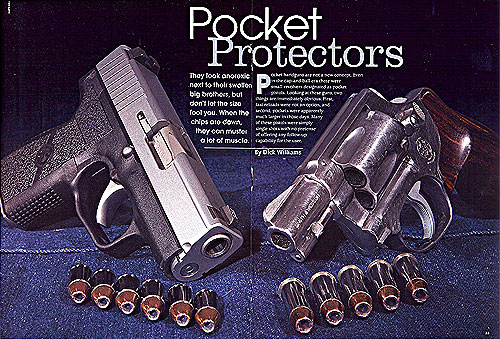

Pocket Protectors

They look anorexic next to their swollen big brothers, but don't let the size fool you. When the chips are down, they can muster a lot of muscle.

Shooting Illustrated, June 2007, p.32 - 37

By Dick Williams

Pocket handguns are not a new concept. Even in the cap-and-ball are there were small revolvers designated as pocket pistols. Looking at these guns, two things are immediately obvious: First, fast reloads were not an option, and second, pockets were apparently much larger in those days. Many of these pistols were simply single shots with no pretense of offering any follow-up capability for the user.

During the latter half of the 19th century, when self-contained cartridges were replacing caps and balls, Smith & Wesson and other manufacturers made some very small revolvers that were the forerunners of today's snub-nose revolvers. As we rolled into the 20th century, several companies such as Colt, and I believe Savage, offered some compact semi-automatic pistols for those choosing not to announce they carried a handgun. But the epitome of old-time pocket pistols for most Americans was the two-shot derringer with over-and-under barrels. Hollywood made these hideout guns famous in numerous Westerns, and even today, cowboy action shoots frequently feature a special event for them. If you're willing to settle for just two shots to resolve hostilities, the old-style derringer with its flat outline and compact size offers advantages unsurpassed by many of today's concealed-carry handguns. However, besides being limited to two shots, these derringers are single-action pistols requiring the shooter to manually cock the hammer each time before firing. They not only lack firepower, they are much slower into action than double-action revolvers.

In the 1930s, many people utilized 2-inch-barreled revolvers. Colts and Smith & Wessons filled the hands of cops, bootleggers and private eyes on the movie screens. Initially, the short barrel was the only real attempt to downsize these revolvers for hideout duty, with nothing being done to reduce frame size and further facilitate pocket carry. Both companies had six-shot revolvers with external hammers, and white the cops were sometimes shown with holsters, I don't ever recall seeing a bad guy draw a short revolver from leather. While longer barreled revolvers were occasionally carried tucked in the waistband, snubbies emerged from a pocket or were sometimes fired from within. At that time, the nylon pocket holster had not yet been invented, and whole a few really clever guys might have utilized a couple pieces of leather inside the pocket to protect their clothes and facilitate getting the gun into action, I doubt this was the case since clothes then were made of heavier material like wool, and fashions seemed to dictate a more casual look.

Smith & Wesson's J-frame revolver reduced both frame size and capacity, giving the savvy shooter a smaller pocket pistol that carried five rounds instead of six. The smaller grip frame further helped conceal the pistol but at the expense of making the gun more difficult to control when shooting the standard 158-grain .38 Special police loads of that era. Subsequent development of more sophisticated self-defense ammunition helped alleviate this problem, but at the time the downsizes frame was a decision that proved to be brilliant over the next several decades. With a couple additional refinements, the five-shot J-frame-size revolver is the pocket pistol of choice for millions today, doing double-duty as the primary self-defense gun in many homes.

One of the other favorite handguns during the early 20th century was the Colt 1911. You couldn't classify it as a pocket pistol, but its flat profile made it more comfortable to carry tucked into a waistband or belt than a revolver. Colt picked up on this market and began producing the Commander. With a slightly shorter barrel and an alloy frame, it was lighter in weight and less bulky than its all-steel big brother, and knowledgeable gunnies capitalized on its virtues. Some cursed the Commander, claiming its alloy frame wouldn't take the abuse of continuous full-power loads. Perhaps someone destroyed a Commander in prolonged firing under a controlled and monitored test program, but I don't remember reading about it Several clever gunsmiths recognized the advantages of customized 1911s and began chopping them to make them more concealable. Ultimately, manufacturers jumped on the bandwagon, and the result is an array of incredibly compact and durable 1911s with 3-inch barrels and lightweight frames made of exotic metals.

Late in the 20th century, a couple of major developments occurred in the handgun world that would bring about a new class of pocket pistols. One was the semi-auto that accepted double-stack magazines, and the other was the use of lightweight polymer frames. Beretta's winning of the U.S. military handgun contract cemented the high-capacity pistol's place in the market, while Glock revolutionized handgun design with high-tech materials. Other companies started manufacturing both wide-body and synthetic-frame pistols, and many produced downsized guns intended for the pocket. While some of these have been quite successful in terms of sales, none are as well suited for pocket carry as the compact revolver, at least in this old dog's opinion. With that thought, let's start by looking at the revolver pocket pistols available on today's market.

Secretive Semis

That brings us to the semi-automatic handguns. Over the last five years, Shooting Illustrated has done a number of articles on 1911s, including some on the ultra-compact .45 and 9 mm pistols. Considering the incredible popularity of the 1911, one would have to consider the small versions as pocket pistol candidates. But as much as I love these guns, I would not select one as my first choice for pocket carry. Having a cocked-and-locked 1911 with its short trigger pull loose in my pocket, particularly a trouser pocket, would make me very nervous. Even a pocket holster doesn't seem to offer enough constraint given the typical body movements one generates in a normal day. In fact, the thought of any semi-auto with a short trigger pull in my pocket gives me chills. That said, there are some I would consider for pocket carry.

Last June, I reviewed in my "Handguns" column a couple of polymer-frame pistols from Kahr and was particularly impressed with the CW9. I've always liked the steel-frame Kahr pistols, but they are rather heavy for the pocket. The polymer CW9, however, weighs less than 16 ounces, putting it in the class of alloy-frame revolvers. Even lighter and more suited for pocket carry is the company's PM9 with a 3-inch barrel and an overall length of 5.3 inches. That's more than an inch shorter than Smith & Wesson's 340PD. The PM9's standard magazine that sits flush with the bottom of the grip frame holds six rounds of 9 mm and keeps the height of the semi-auto to just 4 inches, but the gun also comes with a seven-round extended magazine for those having a little more room in their pockets and the need for someplace to rest their pinky during firing.

Width is an important factor to consider when you are looking for a pistol to carry in your pocket, and with a slide that is a slim .9 inch wide, the PM9 rides nicely in its hiding place without being bulky. The PM9's steel slide has several near-vertical serrations that facilitate manual slide operation, but the edges are relatively smooth to minimize the possibly of snagging the gun while drawing it from the pocket. Like the rest of the pistols in the Kahr lineup, the PM9 is double action only and utilizes the locked-breech design with an internal striker and no external safety. It keeps the pistol streamlined and makes it fast to fire—just pull the trigger—but there is no second-strike capability. If your first round fails to fire, you'll have to manually rack the slide to cock the action. Molded, rather aggressive checkering on the frontstrap and backstrap along with stippling on the grip sides help hold the pistol still in the pocket while offering good control during firing, but since these surfaces are covered by the shooting and during the draw, there is little resistance when removing the gun. The PM9 is a potent little pistol that will fit comfortably in almost any pocket.

<< Go back to Previous Page